|

|

www.hygra.com

|

ANTIQUE BOXES

at the Sign

of the Hygra

2 Middleton Road

London E8 4BL

Tel: 00 44 (0)20 7254 7074

Fax: 00 44 (0) 870 1257669

email:

boxes@hygra.com |

Antique Boxes in English

Society

1760 -

1900

by

Antigone

STYLE, MATERIALS and METHODS

|

The stylistic development of the box in the English home from the middle

of the eighteenth century to the end of the nineteenth century can be summarized

as follows:

-

Rococo c1760,

-

Neo Classical c1780,

-

Neo Classical with diverse influences of shape and decoration c1800-1840,

-

sensible, utilitarian simple shapes, or extravagantly opulent, later

19th century.

There are of course overlaps and individually made boxes, which defy

categorization. I will be dealing with more stylistic detail in the relevant

chapters of the type of boxes namely:

Tea Caddies, Writing

Boxes, Work- Sewing Boxes, Card Boxes,

Vanity Boxes, Jewellery

Boxes, Table Cabinets, and empty Boxes.

|

|

The reason I am using the term boxes in the English home and not English

boxes, is because a number of important boxes were brought to England from

other countries, mainly China and

India. Not only were such boxes highly valued by

the connoisseurs of the time, they also influenced style, techniques and

decoration in England.

It is not always easy to separate style from material and technique as the

one often dictates, or at least influences the other. Furthermore without

an understanding of the methods used by the box makers the exposition of

the stylistic influences has no foundation. Below is a brief listing of the

major characteristics of the working practices of the 18th and

19th century box maker which are apparent to the eye and hopefully

can serve as a guide in dating and placing boxes of the period.

|

|

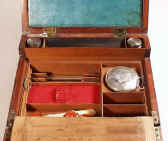

Mahogany Writing Box with Dressing Tray Circa 1800

A mahogany brass bound box which is an example

of a combined dressing case and writing desk. The lift out

dressing tray is fitted for holding a man's grooming accessories. This

is a very unusual arrangement.

|

Writing boxes, document boxes, printing boxes,

gentlemen’s vanity boxes, decanter boxes

and workboxes were made in solid mahogany in the

later part of the 18th century. Occasionally solid oak was used

as in the earlier bible and writing slopes.

The early solid oak bible boxes are described fully in Anthony J.

Conybeare's books.

Trees, Chests and Boxes of the 16th and 17th Centuries

ISBN: 1854211420

Through a sequence of chests, desks and table boxes from c.1550 to

1720, the author illustrates possible timber sources, methods of

construction and decoration, and offers a range of dates between which

each box was likely to have been made.

Here are links to the book page on Amazon

|

|

Solid mahogany continued to be used for writing boxes and other gentlemen’s

boxes until the 1830s. This is mainly because sturdiness was of paramount

importance as officers during the Napoleonic wars, or travelers on the "grand

tour" used such boxes.

From about 1750 thick saw cut veneers were used to cover boxes made in oak,

mahogany or pine. This gave the box maker the opportunity to develop different

techniques. The veneers were both of native and imported woods. This enabled

judicious use of grain, as well as a wider choice of decorative devices.

Edging, banding, cross banding, inlay, stringing and a variety of other methods

were used to enhance the appearance of the box and overcome structural problems.

The most fashionable woods in the late 18th and early

19th century were mahogany, fruitwoods, yew, harewood, satinwood

and partridgewood. Very early in the 19th century and often used

with the earlier woods, kingwood and rosewood were introduced. By the 1830s

amboyna, ebony, coromandel, zebrano and other exotic hardwoods which were

previously mainly used only in Tunbridge Ware,

were used widely by many cabinet makers.

Another group of boxes produced at the end of the 18th and the

beginning of the 19th century were veneered in sycamore or other

light coloured woods. This was to enable painted,

penwork, chinoiserie, decoupage, printed or

other decoration to be applied, often in combinations of different techniques.

The surface of the box was sometimes gessoed and sanded flat before it was

decorated.

With the advent of more mechanization veneers were increasingly cut thinner

and by the middle of the 19th century some timbers were sliced

quite thin. Although many quality boxes were still covered in thick veneers

of exotic woods, walnut started replacing the more expensive woods as the

favorite veneer for boxes. Walnut could be cut very thin which enabled the

box maker to make the best use of the pieces of wood with the richest figure.

Many beautiful boxes were produced in the second half of the 19th

century in walnut veneers, as well as useful pretty boxes in larger numbers

than ever before.

By the end of the century pine boxes were painted to simulate wood grain

as an inexpensive alternative to veneering.

SPECIAL METHODS AND MATERIALS

-

Tunbridge Ware -Boxes made in the area of Tonbridge

in Kent

-

Papier Mâchè

-

Tortoiseshell,

-

Boulle or Buhl

-

Ivory

-

Mother of pearl

-

Straw work

-

Painted, Penwork, Chinoiserie

-

Other Materials

Although synonymous with wood mosaic Tunbridge ware boxes were made long

before this technique and style of decoration was arrived at in the 1830s.

The woodworkers in the area of Tunbridge Wells were making wooden artifacts

even earlier than the seventeenth century when the town became a fashionable

Spa resort. Many early items were turned, but cabinet making was certainly

developed to a very high level by the second half of the 18th

century when box making flourished.

Late eighteenth century boxes are not always easy to identify as Tunbridge

Ware, although the predominant use of yew with fruitwood and holly inlays

of high quality can be a pointer.

|

|

Detail: Figure 485. The

Schiffer Book Antique Boxes Tea Caddies Society

ISBN: 0764316885

Antigone Clarke & Joseph O'Kelly

A slope of delicate workmanship and finesse of

design. It is veneered in harewood with the banding in sycamore. The

structure of the box is almost identical to the previous example,

which makes me think that they were made in the same workshop, if not

by the same hand. The inlay on this slope is exceptionally fine. It is

very much within the neoclassical tradition, but the lightness of

execution and the dot background design lighten the formality of the

classical arrangement. The central oval scalloped wreath design is

elongated upwards which is contrary to tradition. The whole of the top

is edged with a half herringbone banding. There is a very thin line of

half herringbone between the harewood and the sycamore surround. A

truly delightful piece which has been allowed to age with grace. The

inlay, especially the dots which are executed in end grain, are

slightly proud of the surface wood which has settled with age.

13.4" wide. Circa 1780-90

|

Another early type of Tunbridge Ware box was made in sycamore and painted

in primary colours in a naive style depicting scenes with cottages, or flowers.

These boxes were mostly small, sometimes circular or in the shape of baskets.

This kind of work continued into the early part of the 19th century,

mostly for sewing tools enclosed in more ambitious workboxes.

By the end of the 18th century a more refined type of painted

work emerged. Larger and often shaped boxes were produced mostly in the early

part of the 19th century, decorated with

penwork, painting, hand coloured engravings or a combination

of techniques. Again it is not easy to be certain that these boxes were

definitely made or decorated in Tunbridge as the inspirations for the pictures

were often drawn from pattern books available throughout the country. However

even if they were not decorated by the Tunbridge makers many of these boxes

were supplied ‘in the white’ by them, for ladies to decorate at

home.

Tunbridge Ware developed its own characteristic local style by the end of

the 18th century with the development of geometric inlays. The

parquetry and long triangular ‘vandyke’ patterns, which decorate

the Tunbridge Ware boxes of this period, are of such distinctive quality

that they cannot be mistaken for anything else.

The range of wood used to decorate these boxes is unparalleled. It includes:

naturally green fungus-attacked oak, holly, burrs, patterns made in the wood

by fungus infection or peculiar growth, snakewoods (bamboo or palm treated

with black polish to create snakeskin effect) as well as fruitwoods, root

woods and exotic timbers newly arrived in England. The makers laid out the

patterns, using the contrasts and harmonies of the material, with total respect

for its natural beauty and quality. The artistic judgement of the woodworkers

in selecting and arranging these pieces, created some of the strongest and

most beautiful boxes ever made.

Another type of Tunbridge Ware geometric design was created by the stickware

method. This was the gluing and binding together of triangular sticks of

wood in contrasting colours, which were made into rods. The rods were then

sliced into transverse sections and used as decorative veneers of small geometric

patterns. Alternatively the prepared rods were turned to make small objects

or ‘toys.’ It was of paramount importance that the rods to be turned

were prepared with the utmost precision so they could withstand the vicissitudes

of the lathe. Small turned boxes as well as many sewing implements and pens

were made in stickware.

Another variation was the gluing together of sticks in different geometric

shapes, which when set were cut across and used to create patterns of more

variable angles.

In early 19th century boxes, parquetry, vandyke and stickware

are often found in decorative combinations, although boxes from the first

two decades are more restrained and only feature parquetry and vandyke patterns.

The background wood in early 19th century boxes is usually rosewood.

In the late 1820s the small mosaic Tunbridge Ware technique was developed,

became popular by the 1830s and remained so to the end of the nineteenth

century. This technique entailed selecting and sticking thin sticks of wood

of different colour to create a preselected pictorial pattern. When set,

the block was sliced to make veneers repeating the same pattern. The pictorial

veneers were then stuck to the surface of the box. The result was that the

box looked as if it was decorated with inlaid tesserae.

In the best examples of mosaic contrasting colours of wood were used carefully,

to create well defined patterns. The wealth of timber varieties available,

combined with the great skill of the Tunbridge ware craftsmen made this possible.

The timbers used, unlike Italian Sorrento ware, were in their natural colour,

although sometimes this colour was enhanced with chemical processes.

The mosaic technique was used to create geometric border patterns as well

as more ambitious representations of flora, fauna, people and buildings.

Many of the patterns were copied from Berlin woolwork and motifs of Tunbridge

Ware boxes of this period are often referred to as Berlin woolwork designs.

The timbers used as the background veneers for the boxes of this period are

varied. Rosewood was still predominant, but bird’s eye maple, fruitwoods,

ebony and other woods were also used.

The mosaic technique is a very interesting example of the aptitude of the

Tunbridge Ware workers to assimilate and adapt techniques and designs from

other cultures. Stone mosaics were uncovered in the much talked about excavations

of the 18th century. Mosaic covered boxes were known in England

by the beginning of the 19th century by which time exquisite

Sadeli Mosaic had already been introduced from

India.

|

|

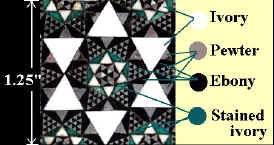

Hygra: A Very Fine Early 19th C. Anglo Indian Ivory and Sadeli Mosaic Tea Caddy.

Detail: the complexity of the mosaic made from precious and

difficult to work materials can be seen on magnified section on the

right. The hexagonal pattern is only 1.25 inches high in reality. For

the design to work the individual mosaic pieces have to be worked to a

very high tolerance.

The ebony and the ivory would first be saw cut and then slowly

scraped to their final profile. This process is very wasteful which

gives an indication of how valued Sadeli work was.

|

The Tunbridge Ware makers must have studied and understood the principle

of this technique as the triangular stickware is an adaptation of Sadeli

in wood. The later mosaic is a further development, rejecting geometric pattern

and adopting Berlin woolwork naturalistic representations, to create an

altogether different effect.

|

Tunbridge Ware Tea Caddy © 1999 Antigone Clarke and Joseph O'Kelly

Detail:

Tunbridge Ware caddies flourished in the middle of the century until

the 1870s. They came in all the shapes already mentioned but with very

elaborate decoration in mosaic marquetry.

There are caddies with castles, flowers, birds, butterflies,

persons, decorated both inside and outside. Sometimes earlier cube

designs are also incorporated in the many happy and not so happy

combinations

|

A maverick among Tunbridge Ware makers was Robert Russell who developed his

own version of marquetry. This was reminiscent of ecclesiastical neo-gothic

patterns and was used either on its own or in conjunction with mosaic work.

In an advertisement of 1863 he claimed his new marquetry to be of "superior

character". Not many pieces of Russell have survived.

Tunbridge Ware makers became very brand conscious by the 1830s and labelled

many of their wares. With a little effort it is not difficult to identify

pieces of Berlin mosaic work. It is much more difficult to identify the earlier

pieces, but this is of no consequence as their quality speaks volumes by

itself.

By the end of the 19th century Tunbridge Ware declined. The

competition from cheaper boxes made from thin veneers and strips of simple

geometric designs proved fatal to the Tunbridge workshops. Not only were

these boxes produced in much larger quantities they were also produced for

a very specific purpose i.e. writing boxes,

work boxes or tea caddies,

which was easier to market to the increasingly wealthy middle classes.

2. Papier

Mâchè

Papier mâchè was the European craftsmen’s answer to

Oriental lacquer. Decorated lacquer furniture

and accessories were becoming increasingly fashionable by the second half

of the 18th century. Natural materials for producing lacquer were

not available in England, but this did not daunt the native makers. Inspired

by the imported wares they set their mind to producing a material, which

would have the same qualities as lacquer.

|

Details: Papier mâchè slope showing A Tea House in Hong

Kong.

|

To this end various attempts were made in combinations of different materials

and varnishes. Papier mâchè substances were known in England

as early as the 17th century when they introduced from Persia

and the east via France.

In England Henry Clay who had mastered the technique by 1772 made the first

papier mâchè boxes and other objects in Birmingham. ‘Clay

ware’ was made by laminating sheets of paper and varnishing the finished

product. This method continued to be used well into the 19th century.

However early in the 19th century other firms introduced the pulped

method, which became very popular especially for smaller items such as boxes.

Early boxes are mostly rectangular, except for tea

caddies, which can also be oval or hexagonal. They are small single container

caddies with fine hinges. The decoration on the 18th century boxes

is in the style of 18th century paintings, Chinoiserie, or very

restrained classical motifs, sometimes incorporating Wedgwood cameos. Boxes

from this period are now rare.

Henry Clay won himself the distinction of Royal appointment, which passed

on to Jennens and Bettridge in 1815 when they took over Clay’s firm.

This firm expanded both the popularity and decorative styles of the medium.

In 1825 mother of pearl inlay was introduced, which was mostly painted over

giving an iridescent effect. This technique was incorporated in painted motifs

of birds, flowers and buildings. Stylised Moorish designs of mother of pearl

and gilding were also created to great effect.

By the middle part of the 19th century, there were a few firms

producing papier mâchè boxes of quality, decorating them with

gilding, painting and mother of pearl. The firm of Lane specialised in fine

reverse painting on glass incorporated on the lid of papier mâchè

and tortoiseshell boxes. These are now pretty rare.

In the 19th century papier mâchè boxes were made

for a variety of purposes. The nature of the material which was by now made

by the pulped method and pressed into moulds enabled the makers to create

interesting shapes such as bombe, concave and sarcophagus, often standing

on plinths or round feet.

Work, jewellery, stationery

and glove boxes as well as tea caddies were very

successfully made in papier mâchè. Because of the fragility

of the material only small writing slopes were made. The main decoration

was on the sloping front, which gave the artists quite a large flat area,

which they often used to great effect.

Table cabinets were made in papier mâchè in impressive architectural

designs, with the doors opening to reveal a series of drawers. They were

decorated throughout and often featured an enclosed writing slope, sewing

tray and jewellery drawer.

Many small boxes especially snuff boxes were made

in the 18th and first half of the nineteenth century. Snuff boxes

were mostly round in the 18th century with painted portraits or

landscapes. In the nineteenth century more novelty shapes were introduced,

such as shoes, bombe, oblong etc. Mother of pearl and inlaid metal decoration

replaced the earlier painted surfaces. In the first two decades of the

19th century round prints were stuck on the tops of round snuff

boxes and hand painted.

Papier mâchè was exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851 by

some of the most notable makers. However after this date the work produced

in the papier mâchè workshops began to decline. Shapes became

heavier and decoration less refined. By the end of the century commercialism

had overtaken the industry and only transfer printed small boxes were produced.

This precious material was used from the later part of the 18th

up to the middle of the 19th century to veneer oak, pine and mahogany

tea caddies, sewing boxes

and sometimes small writing boxes. It was also used in the same way for

small trinket boxes. The boxes made between 1780 and 1820 are of a light

blond colour in very simple shapes, which maximizes the effect of the natural

colour striations in the shell. The wooden structure of the box was first

gessoed in white and then veneered with the thin shell. The effect was

exquisitely subtle and restraint.

The shapes for single caddies were square, hexagonal, or polygonal, with

a flat or pyramid shaped top. Double caddies were rectangular, occasionally

polygonal with a flat top. As the size of the shell was restricting the size

of the possible panels, thin pieces of metal were used to separate ‘book

matched’ patterns on the larger caddies.

Flat sewing boxes were also made during this period and these have four matched

panels on the top separated by metal lines. The larger ones also have a border,

again separated by metal strips. Basically, the larger the box the more it

needed to use decorative tricks to accommodate the smaller size of the shell.

Occasionally the gesso was coloured with ground powder pigment made from

semiprecious stones, which gave the Tortoiseshell veneer a green or red colour.

Such boxes are much rarer than the boxes in natural colour.

During this early period the decoration was restricted to simple silver or

silver plated escutcheons, central plates, loop handles or small finials.

Thin ivory edging lines and facings were also used, although many early boxes

have boxwood facings.

1800-1830

At around 1800 different shapes and styles began to emerge. The green colour

was dropped and the emphasis was no longer on maximizing the effect of the

shell.

Small single tea caddies were made in straight

or sarcophagus shapes with such features as carved edgings, pagoda shaped

tops, stepped lids and pediments. These stood on ivory or silver-plated feet.

Double caddies were made with similar features to the single caddies. Like

the earlier ones these were made using panels joined by metal strips.

A few triple large caddies standing on gilded feet with gilded handles were

made in the early part of the 19th century. They are of sarcophagus

and sometimes slightly bombe shape. These have three panels of shell joined

up at the front. This design was soon dropped, probably as the triple joining

proved difficult to be as effective as the double " book match".

The sewing boxes of the early 19th century are in more complex

shapes than the earlier ones and stand on feet.

Slightly later, from about 1820 the shapes and decoration of Tortoiseshell

boxes became more varied and complex. More stepped spreading supports were

used with serpentine, bombe, concave, sarcophagus and other forms.

New decorative techniques were applied to the new shapes. Embossing, which

had first appeared in simple patterns became rather complex by the 1840s

in "Gothic revival" designs of ecclesiastical tracery.

Mother of pearl inlays of flowers and birds were popular from the second

decade of the 19th century. The best inlays feature pieces with

well defined engraving. Sometimes chinoiserie designs were executed in mother

of pearl, in the whimsy Regency style, which gave them a charming period

look. Fine silver lines were often incorporated in mother of pearl decorated

boxes.

A few pre 1840 tortoiseshell boxes were decorated in fine silver piqué.

Later in the 19th century boxes were mounted with embossed silver

decoration. By the end of the 19th and beginning of the

20th century Tortoiseshell was used in combination with silver

for decorative smaller boxes. Most of these have piqué swags of flowers.

This term is a tribute to the cabinetmaker Andre Charles Boulle who worked

in the late 17th and early 18th century in France. He was ‘ebeniste’

to Louis XIV and perfected the technique of creating patterns in tortoiseshell

and metals or other materials. When early in the 19th century the Prince

Regent purchased some items of French boulle work, English cabinetmakers

seized the challenge and began to produce furniture and boxes using the same

technique.

Most boxes in boulle work are in red- backed tortoiseshell interlaced with

brass in stylised floral patterns. Early ones are sometimes mounted on heavy

gilded feet. They are very different from the English designs, in that the

decorative pattern is more prominent than the figure in the shell.

A word of caution: cheaper versions of boulle work were made using a form

of papier mâchè. The varnish on these is usually crackled. These

boxes are very pretty in their own right, but they are not tortoiseshell.

Ivory was not used extensively in England for the making of boxes. Its most

important use was for veneering the late 18th century tea caddies.

These were hexagonal or octagonal with flat or pyramidical tops. They had

exquisitely made silver hinges, escutcheons, small loop handles, finials

and initial plaques. If they were decorated at all they were decorated in

fine silver or gold piqué, or finely engraved edging lines.

|

|

Sometimes

they had a miniature inset in the center of the large front panel. Occasionally

the panels of ivory were reeded. The inner lids of the caddies were

often made in plain wood, oak, pine or mahogany, which constituted the basic

body of the box.

This is a material often used in inlays but seldom used in its own right.

Some boxes were made of it in the 1830s to 1860s mostly

tea caddies, small perfume bottle boxes, or

necessaires. Very few larger boxes such as sewing boxes or jewellery boxes

were ever made mainly from this material.

Boxes were veneered in squares or diamonds of mother of pearl no bigger than

an inch. Often abalone shell squares were inserted to give interesting colour.

Sometimes these were used to veneer parts of

Tortoiseshell boxes, to create contrasts of

dark and light shell.

The finest and extremely rare examples of mother of pearl boxes were inlaid

in abalone shell. This work was very skilled in that it entailed inlaying

one hard and brittle material into another. The inlays, usually of flowers

are of extraordinary quality. They give life to an otherwise rather cold

material.

Straw workboxes were made in England in the early

part of the 19th century by Napoleonic prisoners of war. By making

and selling these boxes the prisoners were able to improve their living

conditions. The boxes were made out of inexpensive pine, which was then covered

in pictures created by natural and died pieces of straw assembled at different

angles to maximize light values. This delicate work required both considerable

skill and patience.

|

|

Frequently the hinges were made out of twisted circular strips of metal and

were rather rudimentary.

On account of the fragile nature of the material it is unreasonable to expect

to find these boxes in perfect condition. Their interior, which was also

covered in straw work, is often better preserved. The designs are of stylised

flowers, birds, buildings and ships. Sometimes watercolour paintings are

incorporated under glass panels. Although perhaps too frail now for robust

use these wonderful boxes have a great period look and are well worth treasuring

and enjoying for their sheer beauty.

Although the Napoleonic prisoners of war brought straw work to the attention

of the wider public, they were by no means the first exponents of this art

in England. Straw work was practised in Europe as early as the seventeenth

century and straw covered boxes were brought to England first from Holland

and then from France. By the 18th century English makers were

known to use the technique for decorating boxes,

mainly tea caddies.

The caddies dating from the late 18th century are trunk shaped,

or shaped in the preferred tea caddy forms of the period. They were usually

made in pine and veneered with straw work designs, which were first applied

on paper. The designs include stylised flowers, herringbone and parquetry.

These early boxes have a sturdier basic structure than the Napoleonic prisoner

of war boxes and their hardware (hinges, locks i.e.) is of professional quality.

From the second part of the 18th to the middle of the

19th century the English applied arts came under influences both

from the Far East and the classical world of Europe and the Middle East.

Such a wealth of new intellectual, aesthetic and social ideas burst onto

English society that the possibilities of diversification in the arts became

infinite. It was the time of the great romantic poets, expounding new ideas,

of creative novelists, of travelers and merchants bringing back tales of

other lands.

|

|

The group of boxes I am about to discuss, reflect perhaps more than any other

group, the way these influences were translated into box pictorial decoration.

Many of the new designs were received from pattern books, sketches, pictures

or letters.

The published accounts of the first tentative diplomatic steps to the far

east, as well as first hand narratives, conjured up pictures of men, beasts

and plants never previously exposed to such an extend to the non specialist

public. "You in the meantime will be taking a trip into China, I suppose.

How does Lord Macartney go on?" Edmund asks Fanny in Jane Austen’s Mansfield

Park.

Both professionals who specialised in chinoiserie and classical decoration

and private ladies who decorated their own boxes were eager to prove to the

world that they were up to date with their cultural reading. Designs showing

an understanding of classical symmetry, pictures experimenting with peculiar

eastern perspectives "pagodas and the fantastic fripperies" as Hogarth called

chinoiserie, imagined Indian scenes, Gothic ruins and observations from nature

are all to be found on boxes dating from the end of the 18th to

the third decade of the 19th century.

Like most observations, which are perceived second hand, the result is a

distillation of the original, transformed by the perceptions and experiences

of the receiver into his/her interpretation. The pictorial boxes of this

period have a unique and delightful quality, which results from the excitement

of discovery and the eagerness to express it. Each one is a gem of social

history.

The archaeological activities of the time opened up the possibilities of

classical decoration both in terms of pictorial arts and of architectural

forms. Thus we find that a great number of decorated boxes were made in much

more "structural" shapes using pediments, sarcophagus shapes, stepped tops,

panelling, gadrooning, feet and handles harking back to ancient Greece, Egypt

and Pompeii.

Originally all the boxes in this category were varnished. Most of the varnish

has become brittle with dryness and tends to fall off naturally. Caution.

Do not try to take off the varnish, as it is likely to take off the decoration

with it. Just leave it alone.

A. Penwork

Most of the penwork pictures on boxes are derivative of oriental work and

like linear lacquer decoration, they show people and animals in landscapes.

There are also stylised motifs of flora and fauna, pictures ‘observed

from nature’ such as ruins, or natural scenes.

Penwork was often done by people at home and as such an individual’s

idiosyncrasy is often reflected in the work.

The techniques used for this decoration are not always consistent. The boxes

were made in sycamore or other light coloured woods. Then they were either

varnished and then decorated, or gessoed and painted over the white surface.

I have also found another interesting technique used in such boxes: A shallow

embossed imprint of the design made on the wood. By the time the design was

painted in and varnished the surface of the box would again be smooth.

Penwork decoration was often done in black fine lines on a light background.

Sometimes this was done in reverse, i.e. the background was blacked and the

design was light. At times other colour inks, paints, or gold leaf were used

in addition to the black ink. Often hand coloured prints were pasted in the

center of boxes, which were decorated with penwork, borders. The prints were

edged with gold leaf decorated in lines of ink. The whole thing was then

varnished.

B. Painted

Boxes were also painted using paints rather than ink, either direct onto

the wood or on gesso or thin paper. Oriental scenes were not so popular.

Most painted boxes depict naturalistic flowers, classical scenes, animals

or people.

They are even rarer than the penwork boxes and each one has its own individual

merit and beauty. They are some of the most stunning boxes ever made.

C. Chinoiserie

Although the term chinoiserie is loosely used to describe Oriental style

European decoration in boxes in general, what I am going to describe here

are boxes which were made to look as close to oriental lacquer as possible.

|

|

Detail: Polychromed Chinoiserie Tea Chest, Circa 1820

A polychromed tea chest painted in a fluid hand with an exotic

scene. The elongated figures, the inverted flower hats, and the

lightness of execution suggest a knowledge of later more refined

chinoiserie design.

|

Oriental lacquer was built up in many layers on a base of very thin wood.

In England the basic box was made from wood in normal thickness which gave

it sufficient structural support. The undecorated item was then varnished,

or thinly gessoed and varnished.

As sap from the rhus tree, which was used in oriental lacquer, was not available,

the English makers experimented with various lacs, pigments and techniques

as early as the 17th century.

The boxes, which were made in the second half of the 18th and the very early

part of the 19th century, are mostly of black background with gold and colour

decoration. Sometimes red, green or creamy-white was also used as the background

colour. Raised decoration was achieved by building up gesso and painting

over it.

The decoration is of people, buildings and landscapes. The style does not

conform to any western rules of proportion and the peculiar perspective adds

to the charm of these boxes.

Rolled paper and leather were used to cover wooden boxes. As very few types

of such boxes were worthwhile, they will be dealt with in the chapters relating

to the box type. (see tea

caddies)

© 1999-2005 Antigone Clarke and Joseph O'Kelly

|